Most Influential Types of Art and Poetry for Racism

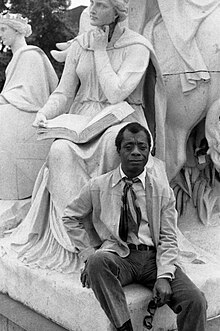

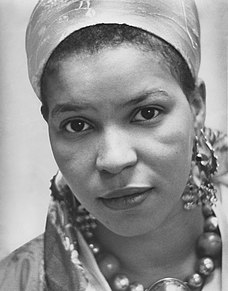

Nikki Giovanni, a participant in the Blackness Arts Motility | |

| Years agile | 1965–1975 (approx.)[i] |

|---|---|

| Country | Us |

| Major figures |

|

The Black Arts Movement (BAM) was an African American-led art movement, active during the 1960s and 1970s.[3] Through activism and art, BAM created new cultural institutions and conveyed a message of black pride.[4]

Famously referred to by Larry Neal as the "artful and spiritual sister of Blackness Ability,"[five] BAM applied these same political ideas to art and literature.[6] The movement resisted traditional Western influences and establish new ways to present the blackness experience.

The poet and playwright Amiri Baraka is widely recognized as the founder of BAM.[7] In 1965, he established the Black Arts Repertory Theatre School (BART/S) in Harlem.[eight] Baraka'south case inspired many others to create organizations across the U.s.a..[4] While these organizations were short-lived, their work has had a lasting influence.

Background [edit]

African Americans had always made valuable creative contributions to American culture. All the same, due to brutalities of slavery and the systemic racism of Jim Crow, these contributions often went unrecognised.[ix] Despite continued oppression, African-American artists continued to create literature and art that would reflect their experiences. A high-indicate for these artists was the Harlem Renaissance—a literary era that spotlighted blackness people.[ten]

Harlem Renaissance [edit]

There are many parallels that tin can be fabricated between the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Arts Movement. The link is so strong, in fact, that some scholars refer to the Black Arts Movement era as the 2nd Renaissance.[11] Ane sees this connection conspicuously when reading Langston Hughes'due south The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain (1926). Hughes's seminal essay advocates that black writers resist external attempts to control their art, arguing instead that the "truly great" black artist will be the one who can fully encompass and freely express his blackness.[11]

Yet, the Harlem Renaissance lacked many of the radical political stances that divers BAM.[12] Inevitably, the Renaissance, and many of its ideas, failed to survive the Great Depression.[13]

Civil Rights Movement [edit]

During the Ceremonious Rights era, activists paid more than and more attention to the political uses of fine art. The contemporary piece of work of those like James Baldwin and Chester Himes would show the possibility of creating a new 'black artful'. A number of art groups were established during this period, such as the Umbra Poets and the Spiral Arts Alliance, which tin be seen as precursors to BAM.[xiv]

Civil Rights activists were also interested in creating black-owned media outlets, establishing journals (such every bit Freedomways, Black Dialogue, The Liberator , The Black Scholar and Soul Volume) and publishing houses (such as Dudley Randall'south Broadside Press and Third World Press.)[4] Information technology was through these channels that BAM would eventually spread its art, literature, and political messages.[xv] [4]

Developments [edit]

The beginnings of the Blackness Arts Motility may exist traced to 1965, when Amiri Baraka, at that time still known as Leroi Jones, moved uptown to establish the Blackness Arts Repertory Theatre/School (BARTS) following the assassination of Malcolm X.[xvi] Rooted in the Nation of Islam, the Black Power move and the Civil Rights Motility, the Black Arts Motion grew out of a changing political and cultural climate in which Blackness artists attempted to create politically engaged work that explored the African American cultural and historical experience.[17] Blackness artists and intellectuals such as Baraka made it their project to reject older political, cultural, and artistic traditions.[xv]

Although the success of sit-ins and public demonstrations of the Black pupil motion in the 1960s may have "inspired black intellectuals, artists, and political activists to form politicized cultural groups,"[xv] many Black Arts activists rejected the non-militant integrational ideologies of the Civil Rights Movement and instead favored those of the Black Liberation Struggle, which emphasized "self-determination through self-reliance and Black control of pregnant businesses, arrangement, agencies, and institutions."[xviii] According to the Academy of American Poets, "African American artists within the movement sought to create politically engaged work that explored the African American cultural and historical experience." The importance that the motility placed on Black autonomy is apparent through the cosmos of institutions such equally the Black Arts Repertoire Theatre Schoolhouse (BARTS), created in the spring of 1964 by Baraka and other Black artists. The opening of BARTS in New York City often overshadow the growth of other radical Black Arts groups and institutions all over the United States. In fact, transgressional and international networks, those of various Left and nationalist (and Left nationalist) groups and their supports, existed far before the movement gained popularity.[15] Although the creation of BARTS did indeed catalyze the spread of other Blackness Arts institutions and the Black Arts move across the nation, it was not solely responsible for the growth of the movement.

Although the Black Arts Movement was a time filled with black success and artistic progress, the movement also faced social and racial ridicule. The leaders and artists involved chosen for Black Art to ascertain itself and speak for itself from the security of its ain institutions. For many of the contemporaries the thought that somehow black people could express themselves through institutions of their ain creation and with ideas whose validity was confirmed by their own interests and measures was cool.[19]

While it is easy to presume that the movement began solely in the Northeast, it actually started out as "separate and distinct local initiatives across a broad geographic area," somewhen meeting to form the broader national movement.[15] New York City is often referred to as the "birthplace" of the Black Arts Move, because information technology was home to many revolutionary Black artists and activists. However, the geographical multifariousness of the movement opposes the misconception that New York (and Harlem, especially) was the master site of the movement.[15]

In its beginning states, the motion came together largely through printed media. Journals such as Liberator, The Crusader, and Freedomways created "a national community in which ideology and aesthetics were debated and a broad range of approaches to African-American artistic fashion and subject field displayed."[xv] These publications tied communities outside of large Black Arts centers to the motion and gave the general blackness public access to these sometimes exclusive circles.

As a literary motion, Black Arts had its roots in groups such as the Umbra Workshop. Umbra (1962) was a commonage of young Black writers based in Manhattan's Lower East Side; major members were writers Steve Cannon,[20] Tom Dent, Al Haynes, David Henderson, Calvin C. Hernton, Joe Johnson, Norman Pritchard, Lennox Raphael, Ishmael Reed, Lorenzo Thomas, James Thompson, Askia M. Touré (Roland Snellings; also a visual artist), Brenda Walcott, and musician-writer Archie Shepp. Touré, a major shaper of "cultural nationalism," straight influenced Jones. Forth with Umbra author Charles Patterson and Charles's brother, William Patterson, Touré joined Jones, Steve Young, and others at BARTS.

Umbra, which produced Umbra Mag, was the first postal service-civil rights Black literary group to brand an affect every bit radical in the sense of establishing their ain voice distinct from, and sometimes at odds with, the prevailing white literary establishment. The attempt to merge a black-oriented activist thrust with a primarily artistic orientation produced a archetype separate in Umbra between those who wanted to exist activists and those who thought of themselves as primarily writers, though to some extent all members shared both views. Black writers accept always had to face the issue of whether their work was primarily political or aesthetic. Moreover, Umbra itself had evolved out of similar circumstances: in 1960 a Black nationalist literary organization, On Guard for Liberty, had been founded on the Lower E Side by Calvin Hicks. Its members included Nannie and Walter Bowe, Harold Cruse (who was then working on The Crunch of the Negro Intellectual, 1967), Tom Dent, Rosa Guy, Joe Johnson, LeRoi Jones, and Sarah E. Wright, and others. On Guard was agile in a famous protest at the United Nations of the American-sponsored Bay of Pigs Cuban invasion and was active in back up of the Congolese liberation leader Patrice Lumumba. From On Guard, Paring, Johnson, and Walcott forth with Hernton, Henderson, and Touré established Umbra.

[edit]

Another formation of black writers at that time was the Harlem Writers Guild, led by John O. Killens, which included Maya Angelou, Jean Carey Bond, Rosa Guy, and Sarah Wright among others. Simply the Harlem Writers Guild focused on prose, primarily fiction, which did not have the mass appeal of poetry performed in the dynamic vernacular of the fourth dimension. Poems could exist congenital around anthems, chants, and political slogans, and thereby used in organizing piece of work, which was non generally the case with novels and short stories. Moreover, the poets could and did publish themselves, whereas greater resources were needed to publish fiction. That Umbra was primarily verse- and operation-oriented established a significant and classic feature of the movement's aesthetics. When Umbra split up, some members, led by Askia Touré and Al Haynes, moved to Harlem in tardily 1964 and formed the nationalist-oriented Uptown Writers Movement, which included poets Yusef Rahman, Keorapetse "Willie" Kgositsile from South Africa, and Larry Neal. Accompanied past young "New Music" musicians, they performed poetry all over Harlem. Members of this group joined LeRoi Jones in founding BARTS.

Jones'south move to Harlem was curt-lived. In December 1965 he returned to his home, Newark (N.J.), and left BARTS in serious disarray. BARTS failed but the Black Arts center concept was irrepressible, mainly because the Blackness Arts motion was so closely aligned with the then-burgeoning Blackness Ability movement. The mid-to-late 1960s was a period of intense revolutionary ferment. Get-go in 1964, rebellions in Harlem and Rochester, New York, initiated four years of long hot summers. Watts, Detroit, Newark, Cleveland, and many other cities went upward in flames, culminating in nationwide explosions of resentment and anger following the Apr 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Nathan Hare, writer of The Blackness Anglo-Saxons (1965), was the founder of 1960s Black Studies. Expelled from Howard University, Hare moved to San Francisco State Academy, where the battle to establish a Blackness Studies section was waged during a five-calendar month strike during the 1968–69 school year. As with the establishment of Black Arts, which included a range of forces, in that location was broad activity in the Bay Surface area around Black Studies, including efforts led by poet and professor Sarah Webster Fabio at Merrit Higher.

The initial thrust of Black Arts ideological development came from the Revolutionary Activity Move (RAM), a national arrangement with a strong presence in New York Urban center. Both Touré and Neal were members of RAM. After RAM, the major ideological strength shaping the Blackness Arts movement was the The states (as opposed to "them") arrangement led past Maulana Karenga. Also ideologically important was Elijah Muhammad's Chicago-based Nation of Islam. These 3 formations provided both way and conceptual direction for Black Arts artists, including those who were non members of these or any other political arrangement. Although the Black Arts Move is often considered a New York-based motility, ii of its three major forces were located exterior New York City.

Locations [edit]

Every bit the movement matured, the ii major locations of Black Arts' ideological leadership, especially for literary work, were California's Bay Expanse considering of the Journal of Blackness Poetry and The Blackness Scholar, and the Chicago–Detroit axis considering of Negro Digest/Black World and Third World Press in Chicago, and Broadside Press and Naomi Long Madgett's Lotus Printing in Detroit. The only major Black Arts literary publications to come out of New York were the short-lived (half-dozen issues between 1969 and 1972) Blackness Theatre mag, published by the New Lafayette Theatre, and Blackness Dialogue, which had actually started in San Francisco (1964–68) and relocated to New York (1969–72).

Although the journals and writing of the motility greatly characterized its success, the movement placed a great deal of importance on collective oral and operation art. Public collective performances drew a lot of attention to the movement, and it was often easier to go an firsthand response from a collective poetry reading, short play, or street functioning than it was from private performances.[xv]

The people involved in the Blackness Arts Movement used the arts as a way to liberate themselves. The movement served as a goad for many different ideas and cultures to come up alive. This was a chance for African Americans to express themselves in a fashion that most would not have expected.

In 1967 LeRoi Jones visited Karenga in Los Angeles and became an advocate of Karenga's philosophy of Kawaida. Kawaida, which produced the "Nguzo Saba" (vii principles), Kwanzaa, and an emphasis on African names, was a multifaceted, categorized activist philosophy. Jones also met Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver and worked with a number of the founding members of the Black Panthers. Additionally, Askia Touré was a visiting professor at San Francisco State and was to become a leading (and long-lasting) poet as well equally, arguably, the most influential poet-professor in the Black Arts motion. Playwright Ed Bullins and poet Marvin X had established Black Arts West, and Dingane Joe Goncalves had founded the Journal of Black Verse (1966). This grouping of Ed Bullins, Dingane Joe Goncalves, LeRoi Jones, Sonia Sanchez, Askia M. Touré, and Marvin X became a major nucleus of Black Arts leadership.[21]

Equally the movement grew, ideological conflicts arose and eventually became besides keen for the move to go on to be as a large, coherent collective.

The Black Artful [edit]

Although The Blackness Aesthetic was first coined by Larry Neal in 1968, across all the discourse, The Black Aesthetic has no overall real definition agreed by all Blackness Aesthetic theorists.[22] It is loosely defined, without any real consensus besides that the theorists of The Blackness Artful agree that "art should be used to galvanize the black masses to revolt against their white capitalist oppressors".[23] Pollard also argues in her critique of the Black Arts Move that The Black Aesthetic "celebrated the African origins of the Black community, championed black urban culture, critiqued Western aesthetics, and encouraged the production and reception of blackness arts by black people". In The Blackness Arts Move by Larry Neal, where the Black Arts Motility is discussed as "aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept," The Black Aesthetic is described by Neal every bit being the merge of the ideologies of Black Power with the artistic values of African expression.[24] Larry Neal attests:

"When we speak of a 'Black aesthetic' several things are meant. First, nosotros presume that there is already in existence the footing for such an aesthetic. Essentially, it consists of an African-American cultural tradition. But this aesthetic is finally, by implication, broader than that tradition. It encompasses about of the usable elements of the Tertiary Earth culture. The motive backside the Black aesthetic is the destruction of the white thing, the destruction of white ideas, and white ways of looking at the globe."[25]

The Black Aesthetic likewise refers to ideologies and perspectives of fine art that eye on Blackness culture and life. This Black Aesthetic encouraged the idea of Blackness separatism, and in trying to facilitate this, hoped to further strengthen black ideals, solidarity, and inventiveness.[26]

In The Black Aesthetic (1971), Addison Gayle argues that Black artists should piece of work exclusively on uplifting their identity while refusing to appease white folks.[27] The Black Artful piece of work as a "corrective," where black people are not supposed to desire the "ranks of Norman Mailer or a William Styron".[22] Black people are encouraged by Black artists that take their own Black identity, reshaping and redefining themselves for themselves by themselves via art as a medium.[28] Hoyt Fuller defines The Blackness Aesthetic "in terms of the cultural experiences and tendencies expressed in artist' work"[22] while some other significant of The Black Artful comes from Ron Karenga, who argues for three main characteristics to The Black Aesthetic and Blackness art itself: functional, commonage, and committing. Karenga says, "Black Art must expose the enemy, praise the people, and back up the revolution". The notion "art for art'south sake" is killed in the process, binding the Black Aesthetic to the revolutionary struggle, a struggle that is the reasoning behind reclaiming Blackness art in club to return to African civilization and tradition for Blackness people.[29] Nether Karenga's definition of The Blackness Aesthetic, art that doesn't fight for the Black Revolution isn't considered every bit art at all, needed the vital context of social bug as well as an artistic value.

Among these definitions, the central theme that is the underlying connectedness of the Blackness Arts, Black Artful, and Blackness Power movements is then this: the idea of group identity, which is divers by Black artists of organizations as well as their objectives.[27]

The narrowed view of The Black Aesthetic, often described every bit Marxist by critics, brought upon conflicts of the Blackness Aesthetic and Blackness Arts Movement as a whole in areas that collection the focus of African culture;[30] In The Black Arts Move and Its Critics, David Lionel Smith argues in proverb "The Blackness Aesthetic," one suggests a single principle, closed and prescriptive in which only actually sustains the oppressiveness of defining race in i single identity.[22] The search of finding the true "blackness" of Black people through art by the term creates obstacles in achieving a refocus and return to African culture. Smith compares the argument "The Black Aesthetic" to "Black Aesthetics", the latter leaving multiple, open, descriptive possibilities. The Blackness Aesthetic, particularly Karenga's definition, has as well received boosted critiques; Ishmael Reed, author of Neo-HooDoo Manifesto, argues for creative freedom, ultimately against Karenga's idea of the Black Aesthetic, which Reed finds limiting and something he can't ever sympathize to.[31] The example Reed brings upwardly is if a Black artist wants to pigment blackness guerrillas, that is okay, but if the Black artist "does so only deference to Ron Karenga, something'due south wrong".[31] The focus of black in context of maleness was some other critique raised with the Black Aesthetic.[23] Pollard argues that the fine art made with the artistic and social values of the Black Aesthetic emphasizes on the male talent of black, and information technology's uncertain whether the movement only includes women as an afterthought.

Equally there begins a change in the Blackness population, Trey Ellis points out other flaws in his essay The New Black Aesthetic. [32] Blackness in terms of cultural groundwork tin no longer be denied in guild to appease or delight white or black people. From mulattos to a "postal service-bourgeois movement driven past a second generation of middle course," blackness isn't a singular identity as the phrase "The Black Artful" forces it to be merely rather multifaceted and vast.[32]

Major works [edit]

Black Fine art [edit]

Amiri Baraka's verse form "Black Art" serves equally ane of his more controversial, poetically profound supplements to the Black Arts Movement. In this piece, Baraka merges politics with art, criticizing poems that are non useful to or fairly representative of the Black struggle. Offset published in 1966, a period particularly known for the Civil Rights Motion, the political aspect of this piece underscores the demand for a concrete and artistic approach to the realistic nature involving racism and injustice. Serving equally the recognized artistic component to and having roots in the Civil Rights Movement, the Blackness Arts Move aims to grant a political voice to black artists (including poets, dramatists, writers, musicians, etc.). Playing a vital function in this movement, Baraka calls out what he considers to exist unproductive and assimilatory deportment shown by political leaders during the Civil Rights Motion. He describes prominent Black leaders every bit being "on the steps of the white house...kneeling between the sheriff'south thighs negotiating coolly for his people." Baraka also presents problems of euro-centric mentality, by referring to Elizabeth Taylor every bit a prototypical model in a society that influences perceptions of beauty, emphasizing its influence on individuals of white and black beginnings. Baraka aims his message toward the Blackness customs, with the purpose of coalescing African Americans into a unified movement, devoid of white influences. "Black Fine art" serves as a medium for expression meant to strengthen that solidarity and creativity, in terms of the Black Aesthetic. Baraka believes poems should "shoot…come at you, dearest what you are" and not succumb to mainstream desires.[33]

He ties this approach into the emergence of hip-hop, which he paints as a movement that presents "live words…and live flesh and coursing claret."[33] Baraka's cathartic construction and aggressive tone are comparable to the ancestry of hip-hop music, which created controversy in the realm of mainstream credence, because of its "authentic, un-distilled, unmediated forms of contemporary black urban music."[34] Baraka believes that integration inherently takes abroad from the legitimacy of having a Blackness identity and Artful in an anti-Black globe. Through pure and unapologetic blackness, and with the absenteeism of white influences, Baraka believes a blackness world tin can be achieved. Though hip-hop has been serving as a recognized salient musical course of the Black Aesthetic, a history of unproductive integration is seen beyond the spectrum of music, kickoff with the emergence of a newly formed narrative in mainstream entreatment in the 1950s. Much of Baraka'southward cynical disillusionment with unproductive integration can be drawn from the 1950s, a period of rock and roll, in which "record labels actively sought to have white artists "cover" songs that were popular on the rhythm-and-blues charts"[34] originally performed by African-American artists. The problematic nature of unproductive integration is also exemplified by Run-DMC, an American hip-hop group founded in 1981, who became widely accustomed subsequently a calculated collaboration with the stone group Aerosmith on a remake of the latter's "Walk This Way" took identify in 1986, manifestly appealing to young white audiences.[34] Hip-hop emerged as an evolving genre of music that continuously challenged mainstream acceptance, virtually notably with the development of rap in the 1990s. A significant and modernistic case of this is Ice Cube, a well-known American rapper, songwriter, and role player, who introduced subgenre of hip-hop known as "gangsta rap," merged social consciousness and political expression with music. With the 1960s serving as a more blatantly racist period of time, Baraka notes the revolutionary nature of hip-hop, grounded in the unmodified expression through art. This method of expression in music parallels significantly with Baraka'south ideals presented in "Blackness Fine art," focusing on poetry that is likewise productively and politically driven.

The Revolutionary Theatre [edit]

"The Revolutionary Theatre" is a 1965 essay by Baraka that was an important contribution to the Blackness Arts Movement, discussing the need for change through literature and theater arts. He says: "We volition scream and cry, murder, run through the streets in agony, if information technology means some soul will be moved, moved to bodily life understanding of what the earth is, and what it ought to be." Baraka wrote his verse, drama, fiction and essays in a fashion that would stupor and awaken audiences to the political concerns of black Americans, which says much almost what he was doing with this essay.[35] It also did not seem casual to him that Malcolm Ten and John F. Kennedy had been assassinated inside a few years considering Baraka believed that every voice of modify in America had been murdered, which led to the writing that would come up out of the Black Arts Movement.

In his essay, Baraka says: "The Revolutionary Theatre is shaped past the world, and moves to reshape the world, using as its force the natural force and perpetual vibrations of the mind in the world. We are history and want, what we are, and what whatever experience can brand usa."

With his idea-provoking ideals and references to a euro-centric order, he imposes the notion that blackness Americans should stray from a white aesthetic in order to find a black identity. In his essay, he says: "The popular white man'south theatre like the pop white homo'south novel shows tired white lives, and the issues of eating white sugar, or else it herds bigcaboosed blondes onto huge stages in rhinestones and makes believe they are dancing or singing." This, having much to practise with a white aesthetic, further proves what was popular in society and fifty-fifty what gild had as an example of what everyone should aspire to be, similar the "bigcaboosed blondes" that went "onto huge stages in rhinestones". Furthermore, these blondes made believe they were "dancing and singing" which Baraka seems to exist implying that white people dancing is not what dancing is supposed to be at all. These allusions bring forth the question of where black Americans fit in the public centre. Baraka says: "We are preaching virtue and feeling, and a natural sense of the self in the world. All men alive in the world, and the globe ought to be a place for them to live." Baraka's essay challenges the idea that there is no infinite in politics or in society for black Americans to make a difference through different art forms that consist of, but are non limited to, poetry, song, dance, and art.

Effects on society [edit]

According to the Academy of American Poets, "many writers--Native Americans, Latinos/every bit, gays and lesbians, and younger generations of African Americans have acknowledged their debt to the Black Arts Movement."[17] The movement lasted for well-nigh a decade, through the mid-1960s and into the 1970s. This was a menstruum of controversy and change in the world of literature. I major change came through in the portrayal of new ethnic voices in the United States. English language-language literature, prior to the Blackness Arts Movement, was dominated by white authors.[36]

African Americans became a greater presence not only in the field of literature but in all areas of the arts. Theater groups, verse performances, music and trip the light fantastic toe were central to the movement. Through unlike forms of media, African Americans were able to brainwash others nigh the expression of cultural differences and viewpoints. In particular, black verse readings allowed African Americans to utilize vernacular dialogues. This was shown in the Harlem Writers Guild, which included black writers such as Maya Angelou and Rosa Guy. These performances were used to express political slogans and as a tool for organization. Theater performances also were used to convey community issues and organizations. The theaters, too as cultural centers, were based throughout America and were used for community meetings, study groups and moving-picture show screenings. Newspapers were a major tool in spreading the Black Arts Motility. In 1964, Black Dialogue was published, making it the outset major Arts movement publication.

The Blackness Arts Movement, although brusk, is essential to the history of the United States. Information technology spurred political activism and employ of speech throughout every African-American community. It allowed African Americans the take chances to express their voices in the mass media as well as become involved in communities.

It tin be argued that "the Black Arts movement produced some of the well-nigh exciting verse, drama, dance, music, visual fine art, and fiction of the post-World War 2 Usa" and that many important "mail service-Black artists" such every bit Toni Morrison, Ntozake Shange, Alice Walker, and August Wilson were shaped by the movement.[15]

The Black Arts Move also provided incentives for public funding of the arts and increased public support of various arts initiatives.[15]

Legacy [edit]

The movement has been seen equally one of the virtually important times in African-American literature. It inspired blackness people to establish their own publishing houses, magazines, journals and fine art institutions. It led to the creation of African-American Studies programs within universities.[37] The movement was triggered by the assassination of Malcolm X.[xvi] Amid the well-known writers who were involved with the motion are Nikki Giovanni, Sonia Sanchez, Maya Angelou, Hoyt W. Fuller, and Rosa Guy.[38] [39] Although not strictly office of the Move, other notable African-American writers such as novelists Toni Morrison and Ishmael Reed share some of its artistic and thematic concerns. Although Reed is neither a motility apologist nor abet, he said:

I recollect what Blackness Arts did was inspire a whole lot of Black people to write. Moreover, there would exist no multiculturalism motion without Black Arts. Latinos, Asian Americans, and others all say they began writing as a result of the example of the 1960s. Blacks gave the case that you don't have to assimilate. Yous could exercise your own thing, get into your own background, your ain history, your own tradition and your own culture. I call back the challenge is for cultural sovereignty and Blackness Arts struck a blow for that.[twoscore]

BAM influenced the world of literature with the portrayal of different ethnic voices. Before the movement, the literary catechism lacked diversity, and the ability to express ideas from the point of view of racial and ethnic minorities, which was not valued by the mainstream at the time.

Influence [edit]

Theater groups, poetry performances, music and trip the light fantastic were centered on this movement, and therefore African Americans gained social and historical recognition in the area of literature and arts. Due to the agency and credibility given, African Americans were also able to brainwash others through different types of expressions and media outlets about cultural differences. The nearly mutual form of teaching was through poesy reading. African-American performances were used for their own political advertisement, organization, and community issues. The Black Arts Move was spread by the use of paper advertisements.[41] The first major arts movement publication was in 1964.

"No i was more competent in [the] combination of the experimental and the colloquial than Amiri Baraka, whose volume Black Magic Poetry 1961–1967 (1969) is one of the finest products of the African-American artistic energies of the 1960s."[17]

Notable individuals [edit]

- Amiri Baraka (formerly LeRoi Jones)

- Larry Neal

- Nikki Giovanni

- Maya Angelou

- Gwendolyn Brooks

- Haki R. Madhubuti (formerly Don Lee)

- Sun Ra

- Audre Lorde

- James Baldwin

- Hoyt Westward. Fuller

- Ishmael Reed

- Rosa Guy

- Dudley Randall

- Ed Bullins

- David Henderson

- Henry Dumas

- Sonia Sanchez

- Faith Ringgold

- Ming Smith

- Betye Saar

- Cheryl Clarke

- John Henrik Clarke

- Jayne Cortez

- Don Evans

- Mari Evans

- Sarah Webster Fabio

- Wanda Coleman

- Askia M. Touré

- Marvin X

- Ossie Davis

- June Jordan

- Sarah E. Wright

- Amina Baraka (formerly Sylvia Robinson)

- Ellis Haizlip

Notable organisations [edit]

- AfriCOBRA

- Blackness University of Arts and Letters

- Black Artists Grouping

- Black Arts Repertory Theatre School

- Black Dialogue

- Black Emergency Cultural Coalition

- Broadside Press

- Freedomways

- Harlem Writers Guild

- Negro Digest

- Organization of Black American Civilization

- Soul Volume

- Soul!

- The Black Scholar

- The Crusader

- The Liberator

- Uptown Writers Movement

- Where We At

See also [edit]

- African-American art

- African American culture

- Africanfuturism

- Afrofuturism

- Black pride

- Négritude

- Progressive soul

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Foster, Hannah (2014-03-21). "The Black Arts Motility (1965-1975)". Black Past. Black By. Retrieved 9 Feb 2019.

- ^ a b c d due east f Salaam, Kaluma. "Historical Overviews of The Black Arts Movement". Department of English, University of Illinois . Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Finkelman, Paul, ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of African American History. Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 187. ISBN9780195167795.

- ^ a b c d Bracey, John H.; Sanchez, Sonia; Smethurst, James Edward, eds. (2014). SOS-Calling All Blackness People : a Black Arts Movement Reader. p. vii. ISBN9781625340306. OCLC 960887586.

- ^ Neal, Larry (Summer 1968). "The Black Arts Move". The Drama Review. 12 (4): 29–39. doi:10.2307/1144377. JSTOR 1144377.

- ^ Iton, Richard. In Search of the Black Fantastic: Politics and Popular Civilization in the Post Civil Rights Era.

- ^ Woodard, Komozi (1999). A Nation within a Nation. Chapel Colina and London: The University Of North Carolina Press. doi:x.5149/uncp/9780807847619. ISBN9780807847619.

- ^ Jeyifous, Abiodun (Wintertime 1974). "Black Critics on Black Theatre in America: An Introduction". The Drama Review. eighteen (iii): 34–45. doi:10.2307/1144922. JSTOR 1144922.

- ^ Muhammad, Khalil Gibran (2010). The condemnation of blackness : race, crime, and the making of modernistic urban America (1st Harvard University Press paperback ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Printing. pp. ane–xiv. ISBN9780674054325. OCLC 809539202.

- ^ Kuenz, Jane (2007). "Modernism, Mass Civilization, and the Harlem Renaissance: The Case of Countee Cullen". Modernism/Modernity. 14 (3): 507–515. doi:10.1353/modernistic.2007.0064. S2CID 146484827.

- ^ a b Nash, William R. (2017). "Blackness Arts Movement". Oxford Inquiry Encyclopedia of Literature. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.630. ISBN978-0-19-020109-eight.

- ^ Rae, Brianna (19 February 2016). "From the Harlem Renaissance to the Black Arts Motility, Writers Who Changed the World". The Madison Times.

- ^ The Harlem renaissance. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1999. OCLC 40923010.

- ^ Fortune, Angela Joy (2012). "Keeping the communal tradition of the Umbra Poets: creating space for writing". Black History Bulletin. 75 (1): 20–25. JSTOR 24759716. Gale A291497077.

- ^ a b c d e f m h i j Smethurst, James East. The Black Arts Movement: Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s (The John Hope Franklin Series in African American History and Culture), NC: The Academy of Northward Carolina Printing, 2005.[ page needed ]

- ^ a b Salaam, Kalamu ya. "Historical Background of the Black Arts Movement (BAM) — Part II". The Blackness Collegian. Archived from the original on April 20, 2000.

- ^ a b c "A Brief Guide to the Black Arts Movement". poets.org. Feb xix, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ^ Douglas, Robert Fifty. Resistance, Uprising, and Identity: The Fine art of Mari Evans, Nelson Stevens, and the Black Arts Movement. NJ: Africa World Press, 2008.[ page needed ]

- ^ Bracey, John H. (2014). SOS- Calling All Black People: A Black Arts Motility Reader. Massachusetts: Academy of Massachusetts Printing. p. xviii. ISBN978-1-62534-031-3.

- ^ "A Gathering of the Tribes" Archived 2016-04-15 at the Wayback Automobile (Place Matters, January 2012) includes biography of Steve Cannon.

- ^ "Historical Overview of the Black Arts Move". Department of English, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- ^ a b c d Smith, David Lionel (1991). "The Blackness Arts Movement and Its Critics". American Literary History. 3 (ane): 93–110. doi:x.1093/alh/3.1.93.

- ^ a b Pollard, Cherise A. (2006). "Sexual Subversions, Political Inversions: Women's Poesy and the Politics of the Black Arts Movement". In Collins, Lisa Gail; Crawford, Margo Natalie (eds.). New Thoughts on the Black Arts Movement. Rutgers Academy Press. pp. 173–186. ISBN9780813536941. JSTOR j.ctt5hj474.12.

- ^ Neal, Larry (1968). "The Black Arts Movement". The Drama Review. 12 (four): 28–39. doi:10.2307/1144377. JSTOR 1144377.

- ^ Neal, Larry. "The Black Arts Movement", Floyd Westward. Hayes Three (ed.), A Turbulent Voyage: Readings in African American Studies, San Diego, California: Collegiate Press, 2000 (third edition), pp. 236–246.

- ^ "Blackness Arts Movement". Encyclopædia Britannica article

- ^ a b Smalls, James (2001). "Blackness aesthetic in America". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Printing. doi:x.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.T2088343.

- ^ Duncan, John; Gayle, Addison (1972). "Review of The Black Artful, Addison Gayle, Jr". Journal of Research in Music Educational activity. xx (ane): 195–197. doi:10.2307/3344341. JSTOR 3344341. S2CID 220628543.

- ^ Karenga, Ron (Maulana) (2014). "Black Cultural Nationalism". In Bracey, John H.; Sanchez, Sonia; Smethurst, James (eds.). SOS -- Calling All Black People: A Blackness Arts Motion Reader. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 51–54. ISBN9781625340306. JSTOR j.ctt5vk2mr.x.

- ^ Kuryla, Peter (2005), "Black Arts Movement", Encyclopedia of African American Social club, SAGE Publications, Inc., doi:10.4135/9781412952507.n79, ISBN9780761927648

- ^ a b MacKey, Nathaniel (1978). "Ishmael Reed and the Black Aesthetic". CLA Journal. 21 (3): 355–366. JSTOR 44329383.

- ^ a b Ellis, Trey (1989). "The New Black Artful". Callaloo (38): 233–243. doi:10.2307/2931157. JSTOR 2931157.

- ^ a b Young, Kevin, ed. (2020). Blackness Poem, African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle & Vocal. Library of America. pp. 396–398. ISBN9781598536669.

- ^ a b c "Popular Music and the Spatialization of Race in the 1990s | The Gilder Lehrman Constitute of American History". www.gilderlehrman.org. July 12, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Amiri Baraka". Poetry Foundation. Oct 31, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ Nielson, Erik (2014). "White Surveillance of the Black Arts". African American Review. 47 (ane): 161–177. doi:x.1353/afa.2014.0005. JSTOR 24589802. S2CID 141987673. Project MUSE 561902.

- ^ Rojas, Fabio (2006). "Social Movement Tactics, Organizational Change and the Spread of African-American Studies". Social Forces. 84 (iv): 2147–2166. doi:10.1353/sof.2006.0107. JSTOR 3844493. S2CID 145777569. Project MUSE 200998.

- ^ Cheryl Higashida, Black Internationalist Feminism: Women Writers of the Black Left, 1945-1995, University of Illinois Press, 2011, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Nelson, Emmanuel Due south., The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Multiethnic American Literature: A — C, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2005, p. 387.

- ^ "The Black Arts Movement (BAM)". African American Literature Volume Guild . Retrieved March six, 2016.

- ^ "The Black Arts Movement (1965-1975)." The Blackness Arts Motion (1965-1975) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed, world wide web.blackpast.org/aah/black-arts-movement-1965-1975.

External links [edit]

- Blackness Arts Repertory Theatre/School

- Black Arts Movement Page at University of Michigan

- Amazing Street arts, Black street Arts Westward: Culture and Struggle in Postwar Los Angeles

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Arts_Movement

0 Response to "Most Influential Types of Art and Poetry for Racism"

Post a Comment